Motion does NOT = Productivity! …

... unless you're riding in the Tour de France

“Keep pedaling as fast as you can” might be one piece of good advice for athletes riding in a cycling race, although there is obviously much more to it.

However, in business processes such as manufacturing lines and product development projects, for example, you will be better served by looking for and eliminating excess motion.

Read on to discover how it’s done.

Waiting and Excessive Motion NVA are two of the more difficult to discern and difficult to correct types of Lean Non-Value-Add. Part of the reason is that at first blush, process owners and production associates tend to view them as “just the way it is,” not as problems to be solved.

As with other types of NVA, the crux of the issue is that excessive Motion and Waiting have the effect of slowing the creation of customer value in the process. They add implicit costs, and thus it is worthwhile to understand them and work to reduce or eliminate their causes.

We explore Excessive Motion NVA here; Waiting NVA is in a companion piece.

σ For reference, all 8 Wastes of Lean are summarized in the article, “VA or NVA: that is the Question.”

Is Motion actually waste? Hint: Yes. It. Is.

Some motion is obviously necessary to complete every process step; however, excessive motion results in Lean waste or NVA. A production worker may move away from the station at which the operation is being performed to pick up a tool, locate a component, or confer with a supervisor. If this occurs once per day, it’s probably negligible. If it’s a frequent occurrence, it is probably Non-Value-Add or NVA; in other words, Waste.

Away from the production floor, Motion NVA can occur in business processes wherein multiple people are involved in product development, service, or financial processes, and possibly located in different buildings or work areas.

An example illustrates the detrimental effects of excessive Motion in a Production process, and how the flow can be streamlined.

Manual Assembly of a Complex Product

An equipment contract manufacturer (ECM, Inc.) began producing a system for a new customer, Spacely Sprocket and Power Controller Corp., a start-up who had previously built 10 prototypes in-house over about six months. Spacely was pushing hard to turn their design into physical units and had used a brute-force, just get it done approach to assembling the prototypes. They had provided two technicians with the product drawings and draft Bill of Material and let them build the units on their own.

After contracting with ECM, Inc. and in preparation for their market launch, Spacely gave ECM a forecast for 488 units to ship in the first quarter of volume production, and a hard order for the first 18 units. ECM rapidly built a new production line to meet the customer’s very short schedule for First Customer Ship.

Spacely had provided one non-functional ‘demo’ unit for ECM’s use in setting up the line, with the caution that “some design changes” to hardware and firmware were still being made and that the units ECM would produce would not look exactly like the demo but were “pretty close.” In hindsight this should have been a warning to hold off a bit on process development. Instead, the ECM project team continued in parallel with Spacely’s ongoing design activity, to hit the aggressive date.

Many concurrent activities were quickly underway in ECM: hiring production operators and a process engineer, bringing in workstations, setting up a process flow, writing process instructions, buying lifting equipment to handle heavy components. Oh, and acquiring from various sources all the hand tools that could conceivably be needed – far more than were needed, it turned out.

A subassembly called the Control Assembly (C/A) was quickly recognized as the process bottleneck, requiring about 3-4 hours to assemble manually based on ECM Engineering’s study of the design. ECM divided the assembly into 5 stations with one operator per station, placed about 4 feet apart on a long worktable so the C/A could move through the line without lifting.

As you can probably deduce from the rapid transition (looking back, hasty may be a better word), the process included many instances of NVA, a fact which was evident in the Gemba Walks ECM conducted in the first few weeks.

Significant Gemba Walk Observations

The Gemba Walks covered the entire line; however, the Control Assembly workstations and operations became the focus as they showed a high level of excessive Motion waste. ECM used Kaizen and Plan-Do-Study-Adjust (PDSA) to identify and eliminate NVA.

Manufacturing, warehouse, program management, engineering, and quality people participated fully.

Significant Motion NVA observations included:

1. Tools located on shelves behind operators. Many extra steps required; operators often interfered with one another.

2. Some tools were needed for more than one operation and were shared. More extra steps or reaching, along with delays (Waiting NVA).

3. All parts were placed on racks above the assembly benches, many too high for operators to reach. Operators collected several pieces at a time, cluttering the workstations.

4. Parts were arranged on shelves in part number order because it was easy for warehouse people to take care of. But that meant assembly operators had to walk around looking for the part they needed.

5. Parts were often delivered to the production floor in shipping boxes and cartons to minimize warehouse personnel work. Assembly workers sometimes had to move from their workstations and then uncover boxes and cartons to find a part.

Kaizen–PDSA: Changes to eliminate Excessive Motion NVA

Here is the high-level view of actions taken during the first 15 weeks of production ramp-up to reduce Motion NVA. The full list was over 30 actions.

- Identify the tools needed to perform each operation; place only those tools at the station.

- Move all tools, parts, equipment not required for assembly out of the line, dramatically reducing clutter.

- Locate components needed for each assembly station directly in front of the station and place them in order of their use.

- Remove components from packaging in the Warehouse before delivering to Production.

- Establish kanban for components, instead of stocking weeks’ worth of parts near the workstations.

- Convert the line operation to a pull line with kanban between process steps to minimize work in process (WIP) between operations.

- Review Warehouse and material handling procedures and make changes to conform to the kanban sizes for each operation.

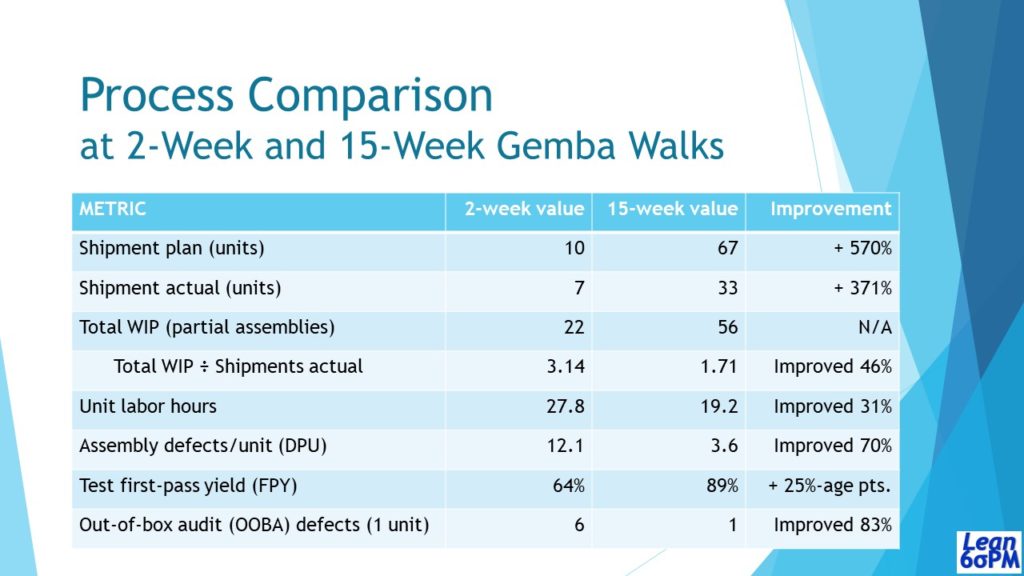

This table shows the improvement achieved in several key ECM Inc. process metrics over the first quarter of production of Spacely’s product.

Gemba Walks allowed process owners to identify areas of concern. Extensive use of Kaizen and the PDSA framework drove the resulting performance gains.

Summary of After-Action Review

The actions ECM took to improve the process flow and to minimize NVA would normally be performed before ever putting the first workstation or tool on the production floor. ECM, in their After-Action Review (AAR), identified that deficiency as the overriding cause of poor startup performance. To their credit, they put corrective actions in place quickly, and continued to monitor the Gemba throughout the life of the Spacely contract.

The table nearby shows the improvement in process metrics that resulted from the kaizen. Shortages of 3 key components (consigned by Spacely) held shipments well below the original plan (33 actual vs. 67 planned in week 15). Even so, significant improvements to line WIP:Shipment ratio, unit labor hours, assembly defects, and test yield were achieved while increasing weekly production output nearly 400%.

Although ECM and Spacely achieved impressive gains in the first quarter over an admittedly poor start, their ultimate objectives for those key process metrics were higher still. And over the course of the next 18 months, Spacely and ECM collaborated to release two significant upgrades to the original product, in those cases designing the new process flows and operations before converting the line.

Remember, kaizen is a continuous improvement practice, not once and done, and thus kaizen continued routinely on the new product versions.

If you haven’t figured it out already, the irony of the Lean Six Sigma philosophy is that as hard as we work at eliminating NVA, reducing variation, and improving quality, we’re never likely to say “Now we are lean and our quality is 6-sigma. We can finally rest!”

Welcome to The Never-Ending Story!

Dann Gustavson, PMP®, Lean Six-Sigma Black Belt, helps Program Managers and their teams achieve superior results through high-impact program execution. Prepare, structure, and run successful programs in product engineering, manufacturing operations (including outsourcing), and cross-functional change initiatives.

Contact Dann@Lean6SigmaPM.com.