Attention, Top 10% PMs: 3 Tools to Help You Avoid Delays and Cost Overruns

The team was cruising along on an advanced technology way-cool product development project. On a random Tuesday morning, though, BAM!! An unexpected supply problem blew up their schedule!

Couldn’t happen to you? Great! But maybe bookmark this article just in case…

Execute for Success; Adjust when Events Dictate

First, some background. As success-oriented PMs, we know our job is to move our programs and projects forward by setting and then executing the plan while addressing problems on the path to completion. To that end, let’s explore and learn to use three non-traditional but superb program management tools to address and resolve project problems when they occur.

These tools come from the Lean Six Sigma methodology. The post, “VA or NVA: That is the Question,” provides an overview of the 8 Wastes of Lean for production processes and other business functions including (as it turns out) program and project management. If you’re not familiar with Lean methods and terms, note that VA stands for Value-Add, and NVA for Non-Value-Add. NVA is synonymous with Waste in the Lean Six Sigma framework.

When we find NVA or Waste, we work to reduce or eliminate it, often by using the tools called Kaizen, Jidoka, and Heijunka. Although the tools were originally developed for production line applications by Toyota and other manufacturers, I have found they can readily be put to use when running engineering, operations, and other technical process flow oriented projects.

Think of them this way.

Kaizen is a process improvement technique, sometimes translated as “break down to make better.”

Jidoka means briefly stopping the process as soon as a problem is detected, to apply a correction and then solve the problem.

Heijunka involves adjusting the staff levels across process steps to smooth the workload.

Read on to discover how one of my New Product Introduction program teams used these three techniques to resolve a component supply problem that threatened a three-month schedule delay.

Like many other aspects of Lean Six Sigma, the terms used are Japanese words owing to the heavy Toyota influence, and often cause confusion when first introduced in English-speaking businesses. Don’t get hung up on the words for now; with use, they will become more familiar.

“Waiting” isn’t a Task in the Gantt Chart!

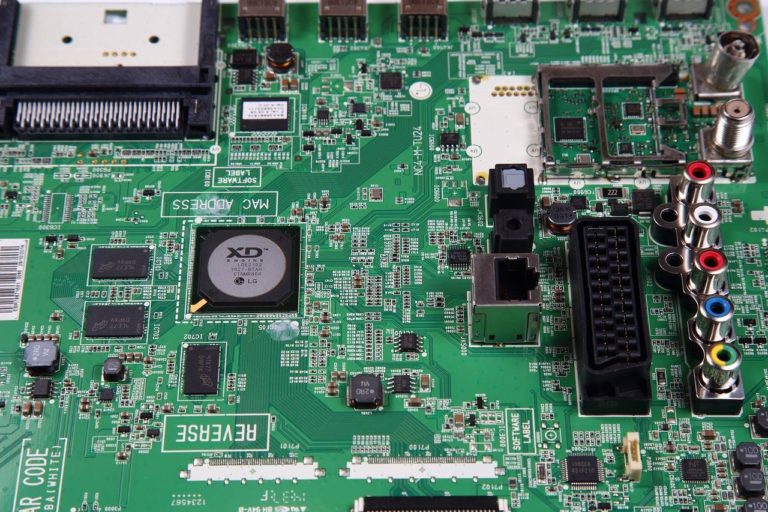

We were developing a new product, a precision electromechanical instrument, code-named Sponge Bob (Techies love cartoon code names, for some reason!). We were approaching the first planned design release. One major element of the new product was a complex printed circuit board (PCB), the Patrick board. The Patrick board design included a commercial off-the-shelf Communication IC in a 48-QFP package, used in 4 locations on the board. (QFP stands for Quad Flat Package)

The team’s Supply Chain associate placed orders for all parts including the Comm IC chips for the Patrick board to prepare for a 50-piece Engineering build planned to start 2 weeks later. In doing so, she found that the 48-QFP version called out in the bill of material had a 12-week lead time.

She statused the PM about the chip delivery problem. Since the Engineering build was a critical path task, the unanticipated IC chip lead time would create a minimum 12-week slip for the entire program!

NOT ACCEPTABLE!!

Jidoka – Kaizen – Heijunka – Oh My!

Or, 3 Superb Program Management Tools

The Program Manager, Buyer, and PCB Design Engineer work together to evaluate possible solutions to the Comm IC lead time, trying to keep the overall program on schedule.

The PM (one of my direct reports) immediately invoked Jidoka, stopping the project briefly to address the schedule problem, and pulled the team together that morning. The Sponge Bob team used Kaizen to find a solution to the IC lead time problem that could mitigate the 12-week program delay. Kaizen embodies a discipline called Plan-Do-Study-Adjust (PDSA) to decide what actions to take and carefully review the results (Plan – Do), then determine if the problem is solved or if another PDSA cycle is needed (Study – Adjust). Much better than guessing, hoping, or shotgunning.

In the Plan phase of PDSA, the team investigated alternatives and found that the chip they required was available in a different package style, called 54-TSOP, with a lead time of 3 days from a distributor. The TSOP (Thin Small Outline Package) package is slightly larger than the QFP and has 54 pins instead of the 48 for the QFP, so could not be directly substituted onto the Patrick printed circuit board (PCB). However, there was a workaround, described below.

This is the Do phase of PDSA. The Buyer ordered the IC chips in both package styles, and the team decided to build 50% additional prototype PCBs for Verification testing. The PCB fabs were ordered with delivery promised in 1 week.

The workaround was this. The board layout engineer designed an ‘interposer’ PCB allowing them to solder the TSOP chip onto the interposer, and then attach the interposer to the Patrick PCB on the QFP footprint. They requested the PCB fab supplier to produce a small quantity of interposers concurrently with the Patrick PCBs.

On to the PDSA Study phase. The team made use of level-loading (Heijunka) and identified a portion of the Verification tests which would not be affected by using the TSOP package Comm chips. They set up and ran those tests on the first-assembled Patrick boards, the ones with the interposer-mounted TSOP parts. After the QFP chips were received and the as-designed boards assembled, the remaining Verification tests were conducted on those production-level Patrick boards.

In the PDSA Adjust phase, the team reviewed all Verification test results against the test protocol to make certain that the use of the alternate Comm IC in specified tests was valid, or whether any repeat / regression testing would be needed in order to pass Verification. Seeing all tests were acceptable, Verification was signed off and the Sponge Bob project proceeded to system integration, manufacturing readiness, and other project release, closeout, and transition tasks.

You have most likely figured out that use of the alternate Comm IC package and interposer design was an unplanned set of tasks that added a few days to the critical path. However, taking that action avoided the extended waiting time (“waiting” is NVA, right?) by enabling many Engineering Verification tests to be conducted earlier using the alternate chip package with interposer.

Thus, the Verification completion date slipped by only 8 days, rather than the 12 weeks expected based on 48-QFP lead time. Remaining tasks were scrutinized and replanned to recover the 8 days and keep the target program completion date.

Summarize What Happened

Let’s conduct a mini-After Action Review or Lessons-Learned on this part of the Sponge Bob program, looking at what the team did and what they didn’t do.

“Didn’t do” first. Nobody demanded to know whose fault the problem was. They did not blame R&D for ‘foolishly’ selecting a long-lead part for the Comm IC. They didn’t try to strong-arm the Comm IC supplier to try to get preferential treatment with or without premium pricing. Nobody ran and escalated the problem to the executive leadership team hoping the VPs would take over the decision-making.

Neither did they just blithely accept the delay.

Then what did the team do? The PM proactively stopped the project – briefly – to focus team effort on the problem and methodically work on possible solutions. (The project actually was stopped for less than one day.) They arrived at a creative solution with multiple team members contributing. They treated ‘their project’ as a process and employed process improvement techniques from outside the established PM body of knowledge, and with which they already were familiar.

Through it all, they kept management informed of the problem, their actions, and finally the solution.

Why Not Become a Top 10% PM?

Your purpose as the Project Manager, whether for a single project or a complex program involving multiple projects, is two-fold.

The first and obvious purpose is to execute your project(s) to completion. All PMs do this.

The second and perhaps not so obvious purpose is to advance the practice of project and program management by identifying aspects of project execution, adaptation, and control that could be done better and that go beyond “In Scope, On Time, and Under Budget.”

An open secret: Most PMs don’t do this!

The Top 10% of PMs do this routinely, bringing in methods from Lean Six Sigma, psychology, sports training, perhaps artificial intelligence (AI), maybe military strategy, and elsewhere when called for. They network with people from other disciplines in and outside their company. They attend lectures and webinars covering a wide range of subjects. They read books. They try out ideas gleaned from any of these sources to see what works.

Learning and using techniques from outside the traditional PM realm can improve project performance, program benefits, and business results. It also leads to the happy side benefit of helping you (the PM) and your key team members develop and demonstrate the skill breadth that leads to career advancement.

When you’re planning and running high-impact programs, don’t settle for “That’s good enough” or “That’s just the way it is.”

Be Proactive, Get Creative, and Aim for EXTRAORDINARY!

Dann Gustavson, PMP®, Lean Six-Sigma Black Belt, helps Program Managers and their teams achieve superior results through high-impact program execution. Prepare, structure, and run successful programs in product engineering, manufacturing operations (including outsourcing), and cross-functional change initiatives.

Contact Dann@Lean6SigmaPM.com.